BLOGCULTURE PARFUM

SCROLL

SCROLL

Bergamot is an essential material in today’s perfumes due to its fresh, zesty smell. Yet, as all citrus fruits, it is at the center of regulatory issues. What are the solutions that will enable perfumers to keep using it?

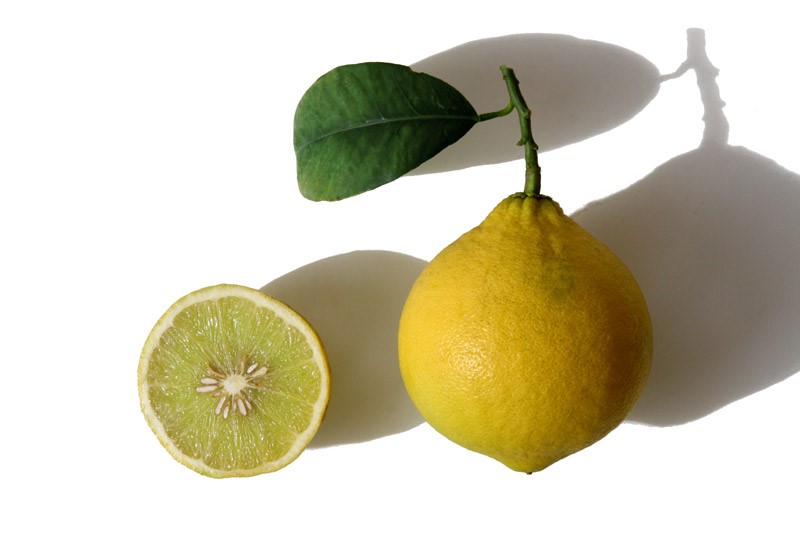

Grown mainly in southern Italy (90% of the world’s tonnage), bergamot comes more precisely from the region extending from Reggio Calabria along the Strait of Messina to the Ionian Sea (Sicily, though very close by, does not grow it due to less favorable conditions of humidity). Also grown in Brazil and Côte d’Ivoire, bergamot measures about 10 centimeters wide and is green before it turns yellow. It has a thick smooth skin and weighs between 80 and 200 grams. Its three varieties are called Castagnaro, Feminello and Fantastico.

The bergamot tree is a small tree of the Rutaceae family (commonly known as the citrus family) whose Latin name is Citrus Aurantium ssp. Bergamia. It produces highly scented white flowers, a very small percentage of which will bear fruit. It results from a cross between a bitter orange tree and a lime tree but could also come from a cross between a bitter orange and a lemon tree.

The bergamot tree is a small tree of the Rutaceae family (commonly known as the citrus family) whose Latin name is Citrus Aurantium ssp. Bergamia. It produces highly scented white flowers, a very small percentage of which will bear fruit. It results from a cross between a bitter orange tree and a lime tree but could also come from a cross between a bitter orange and a lemon tree.

When and where it was originally planted in Europe is uncertain. According to the first theory, bergamot gets its name from the city of Berga, north of Barcelona, where it was supposedly grown when Christopher Columbus returned from the Canary Islands. According to the second theory, its name comes from the Turkish “berg-armadé” or “the pear of the Lord” (due to its shape). Crusaders supposedly brought the fruit back from the Orient.

Harvesting is done by hand from early December to March. The fruit pickers wear gloves so as not to damage the peels. About 200 kg of fruit is required to obtain 1 kg of essence, a yield of 0.5%. Essential oil production in Italy is on the order of 100 tons/year. Between the beginning and the end of the harvesting period, there are relatively significant olfactory differences. Generally greener in the beginning, then increasingly fruity and floral, the essential oils obtained are commonly mixed so as to homogenize the quality of the harvest: this is referred to as the communelle.

As most raw materials from the citrus family, several parts of the tree are treated for perfumery: the branches, the leaves and of course the fruit, which contains essential oil in the many oil-bearing vesicles of the peel.

Essential oil of bergamot, of a yellowish green to brown green color, is obtained through cold-pressing of the pericarp (or peel) of the fresh fruit with peeling machines, huge rollers whose inside wall is covered with pointed spikes that stick into the fruit. The bergamot petit-grain essence is obtained by distilling the flowering tops and the leaves of the tree.

For a very long time the bergamot peel was also put to other uses. In fact in the 18th century, different writings mention the use of bergamots, small boxes of the same name as the fruit. These boxes were made mainly in Grasse, already reputed for its perfumes, and in the Italian regions of Venetia, Calabria and Sicily.

Glover-perfumers, overburdened by too many taxes on leather, are the ones who started to make bergamot boxes. The molded cardboard technique was very widespread in Provence in the 18th century. It was rather simple and cheap to make a bergamot box. You just had to cut a fruit in two and gently remove its pulp so as not to damage the peel. The shell obtained was then plunged in water for a length of time, then turned over and left to dry in the sun on a mold that gave it shape as it dried. After buffing, the half peels were decorated with a dry point, then the two halves of the peel fit together to create a small box.

Originally, only the peel made up the box, but later, to deal with its vulnerability, Grasse craftsmen came up with an embellishment to cover it, most often papier-mâché. The boxes could then be painted and polished.

The bergamots were often gifts from suitors. Women kept their gloves, ribbons and handkerchiefs in them. These delicately scented boxes were precious gifts offered for Christmas or New Year’s, or were purchased as a souvenir of a stop in Grasse. Grasse craftsmen themselves offered them to their best customers.

The Musée International de la Parfumerie, in Grasse, has an astonishing collection of them today, evidence of this very original use of the fruits of the bergamot tree.

The fruit is not well suited to consumption due to the acidity and bitterness of the pulp, but it is used to flavor tea (notably Earl Grey), Moroccan tajines (where it is candied), and the well-known bergamot sweets made in Nancy. Gilliers, chief of staff of the king of Poland and duke of Lorraine Stanislas Leszczynski (1677–1766), came up with a tart barley candy with bergamot essence that quickly became the favorite sweet of King Stanislas. In 1857 bergamot, long set aside for the exclusive use of the royalty, became a Nancy specialty for the general public thanks to the sweets maker Lillig, who gave it its square shape.

The fruit is not well suited to consumption due to the acidity and bitterness of the pulp, but it is used to flavor tea (notably Earl Grey), Moroccan tajines (where it is candied), and the well-known bergamot sweets made in Nancy. Gilliers, chief of staff of the king of Poland and duke of Lorraine Stanislas Leszczynski (1677–1766), came up with a tart barley candy with bergamot essence that quickly became the favorite sweet of King Stanislas. In 1857 bergamot, long set aside for the exclusive use of the royalty, became a Nancy specialty for the general public thanks to the sweets maker Lillig, who gave it its square shape.

From a chemical point of view, bergamot essence is mainly made up of limonene, linalool and linalyl acetate. It also contains neral and geranial, responsible for the bright green citrus note. Finally it also contains furocoumarins, in particular bergaptenes, which make it a photosensitive product. These substances are eliminated through fractional distillation (essential oil of bergaptene-free bergamot, which is called desensitized or even de-furocoumarinized), notably when used in dermocosmetology.

From a chemical point of view, bergamot essence is mainly made up of limonene, linalool and linalyl acetate. It also contains neral and geranial, responsible for the bright green citrus note. Finally it also contains furocoumarins, in particular bergaptenes, which make it a photosensitive product. These substances are eliminated through fractional distillation (essential oil of bergaptene-free bergamot, which is called desensitized or even de-furocoumarinized), notably when used in dermocosmetology.

According to Emmanuelle Fourmon, in charge of regulatory affairs at Payan Bertrand, “The photo-toxicity of bergamot, mainly do to 5-MOP (5-methoxypsoralen) of the furocoumarin family, implies a strict regulatory framework in order to control the use of this essential oil in cosmetic products. At the European level, the Cosmetics Regulation (1223/2009/CE) in fact prohibits the use of 5-MOP (and other furocoumarins) in cosmetic products (Annex II/358), except for normal amounts in the natural essences used. In sun creams and tanning products the furocoumarines must be present in amounts of less than 1ppm.

“On the international level, the IFRA recommendations are similar and for essential oils containing furocoumarins they set a maximum concentration of 15 ppm of 5-MOP in the finished product (applied to skin exposed to the sun and without rinsing). There are also special restrictions established by IFRA for the essential oil of bergamot obtained by expression, set at 0.4% in the finished product for use on the skin.”

So today it is possible to obtain essential oils of bergamot without furocoumarins. As part of a formulation with a significant percentage of bergamot essence, this is the solution most often proposed to perfumers. In fact, no synthetic substance or isolated ingredient, such as limonene, linalool or linalyl acetate – its main constituents – is able, as of now, to substitute totally for natural bergamot extract. Thus the latter, after treatment, remains very commonly used in perfumery.

Fresh, sparkly, floral (thanks to linalyl acetate), bergamot is one of the most often used products in perfumery. Very present in the citrus family, characterized by zesty citrus notes, it is a top note emblematic of current as well as traditional perfumery. It is notably combined with orange, lemon and mandarin (much more rarely with citron) as well as with bitter-orange petit-grain and neroli, a close olfactory cousin, in Eaux de Cologne.

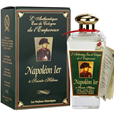

An interesting and little known Eau de Cologne is Eau de Cologne de Napoléon à Sainte-Hélène. From body rubs to the consumption of what he considered a scented liqueur, Napoleon was a real fan of Eau de Cologne, as evidenced by a delivery made in October 1808, notably including 72 bottles of the scented water. It was then made up of esprit-de-vin, melissa water and rosemary esprit, combined with the essence of bergamot, neroli, citron and lemon. This Eau de Cologne was a descendant of Aqua Mirabilis or Eau admirable.

Created around 1693 in Cologne by a certain Giovanni Paolo Feminis, Aqua Mirabilis was thus named because of its therapeutic virtues (it was recommended for treating wrinkles, stomach aches, dizziness, congestion, insect bites). On his death in 1736, Feminis supposedly bequeathed the secret of his formula to his nephew Jean-Marie Farina, who made the eau famous in Cologne then in France and throughout the courts of Europe (in fact later it became L'Eau de Cologne de Jean-Marie Farina from the Roger & Gallet house and is still sold today).

Created around 1693 in Cologne by a certain Giovanni Paolo Feminis, Aqua Mirabilis was thus named because of its therapeutic virtues (it was recommended for treating wrinkles, stomach aches, dizziness, congestion, insect bites). On his death in 1736, Feminis supposedly bequeathed the secret of his formula to his nephew Jean-Marie Farina, who made the eau famous in Cologne then in France and throughout the courts of Europe (in fact later it became L'Eau de Cologne de Jean-Marie Farina from the Roger & Gallet house and is still sold today).

In 1815, when Napoleon was exiled to Saint Helena, his Eau de Cologne supplies were insufficient. He called upon his servant, the Mamluk Ali to make him his favorite cologne. As precisely as possible, Ali reproduced an Eau de Cologne using the plants he found on the island.

How do we know this story? It happens that the Mamluk Ali was in reality called Louis-Etienne Saint-Denis and that he was from Versailles. André Damien, a Napoleon buff and mayor of Versailles, acquired the personal documents that had belonged to the Mamluk and found a piece of paper upon which was written what resembled a perfume formula. In 1991, he took the paper to Jean Kerléo, founder of the recently opened Osmothèque, to ask him what exactly was written. Jean Kerléo confirmed his hunch: the formula for an Eau de Cologne. Damien turned the formula over to Jean Kerléo, who reproduced it with great awareness of its historical interest. It became one of the star perfumes of the Osmothèque.

Frequently used in Eaux de Cologne, bergamot is also often used in top notes to lighten up the kick-off of a perfume from another family. Nuit de Chine (1913) from Parfums de Rosine (Paul Poiret) is a good example of a sweet amber-y fragrance that starts with a wisp of bergamot.

It is also present in many fragrances, particularly in the “floral green” fragrance family, the first being the very original Vent Vert from Balmain (1945), created by Germaine Cellier. Directly descended from this, there are also Guy Laroche’s Fidji (1966) and Chanel N°19 (1970), respectively created by Joséphine Catapano and Henri Robert. Bergamot is also found in men’s perfumes such as Yves Saint Laurent’s L'Homme and the all-new Sauvage from Parfums Christian Dior (2015).

Bergamot should not be reduced to a top note. It plays a greater role as a binder of accords and an exceptional natural solvent: it also plays a magnificent role in Guerlain’s Shalimar (1925).

Finally bergamot is well liked for its modern aspects: neither too feminine nor too masculine, it adapts well to the legitimate temptation of “mixed” notes, one example being Bergamote 22 created by LE LABO.

Used and highly appreciated for centuries in perfumes, and thanks to current fractioning techniques making its use possible in spite of regulatory constraints, bergamot is a must ingredient still today in modern compositions. Its floral-fruity duality makes it unique and precious to all perfumers.

Clémence Decolin

GO BACK TO THE BLOG